George Peter Murdock

1897 — 1985

Professor of Anthropology, Yale University

Africa. Its Peoples and Their Culture History

New York. McGraw-Hill. 1959. 456 p.

Explore also (a) the SemanticAfrica Peoples Vocabulary

(b) the Southern Nigerians mind-mapping diagram

Part Seven

Cultural Impact of Indonesia

— 31 —

Southern Nigerians

The tropical forest which blankets the Congo Basin also extends along the Guinea coast of West Africa. Archeological research reveals essentially the same distribution for the prehistoric hunting and gathering cultures known collectively as Sangoan. Since these are associated in the Congo with peoples of the Pygmoid race, many authorities have assumed that Pygmies once inhabited the Guinea coast as well. No remnants, however, are found there today. Negroid peoples speaking languages of the Nigritic stock occupy the costal zone as exclusively as they do the interior. The present chapter deals with the inhabitants of Southern Nigeria. These Negro peoples for the most part speak languages of the Kwa subfamily of the Nigritic stock, but the Bantoid subfamily prevails in the extreme east, and the Ijaw tribe constitutes the only representative of the Ijaw subfamily. Analysis of the culture of the area will be faciitated by a classification of the components societies into five clusters.

Fine Examples of Ife Yoruba Sculpture.

(Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History.)

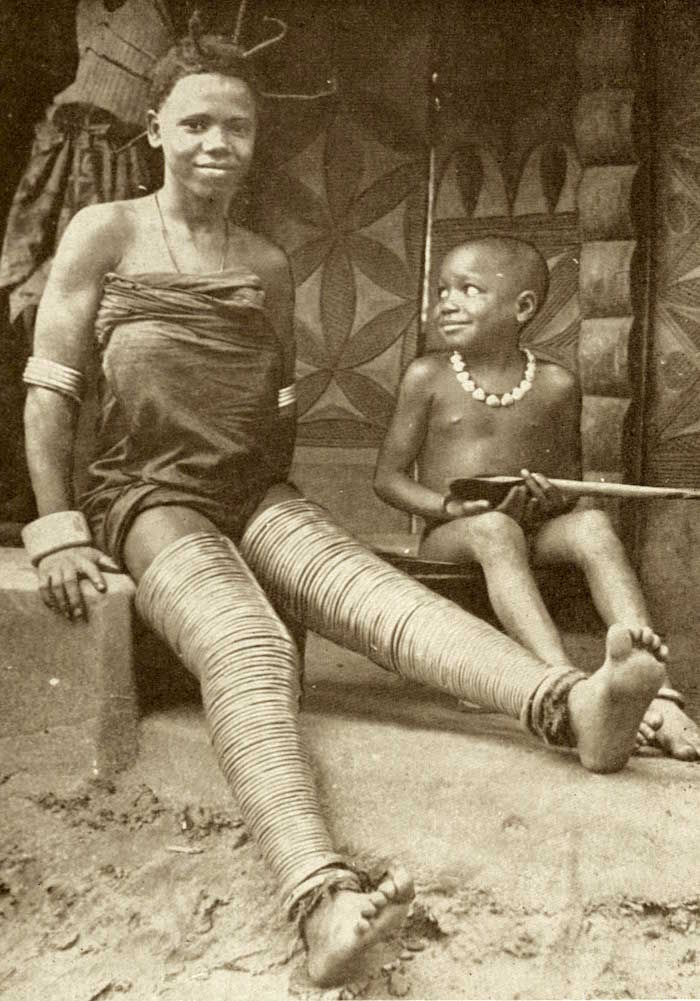

Onitsha Ibo Girl with Characteristic Leg Bangles.

(Courtesy of British Information Services.)

Bantoid Cluster

All the tribes of this cluster speak languages of the Bantoid subfamily of the Nigritic stock. It is probable that they descended from the Nigerian plateau to the adjacent coast upon acquisition of the Malaysian food plants from the east.

- Anyang (Anjang, Bascho), with the kindred Banyang (Banjangi, Konguan, Manyang). They number about 50,000.

- Boki (Nki), with the Bete, Uge, and Yakori (Yakoro). They were reported in 1921 to have a population of 92,000.

- Ekoi, embracing the Akaju (Ahaju), Atam, Ejagham (Ekoi proper), Keakn, Manta, Nde (Ndei), Obang, Olulumaw, and other subtribes. Their population was reported as 90,000 in 1921.

- Ibibio (Agbisherea), with the Anang, Andoni, Efik, Eket, Enyong, lbeno, and detached Abuan. They number slightly more than a million.

- Mbembe, with the Adun (Arun), Igbo, Oshopong (Eshupum), and other small groups. They were reported in 1921 to number about 38,000.

- Ododop (Erorup), with the Korop (Korawp) and Okoiyang. They number about 5,000.

- Orri, embracing the Effium, Okporo-Mteze, and Ukelle. They number about 75,000.

- Yako, with the Abayong (Abaiyonga), Abine (Abani), Agoi, Akunakuna (Agwaaguna), Asiga (Essiga), Ekumuru (Ikumunu), Ekuri, Enna, and Uyanga. They number about 40,000.

Idoma Cluster

The tribes of this cluster all speak languages of the Kwa subfamily of the Nigritic stock, but whether they are affiliated primarily with the Nupe or the Yoruba branch of this subfamily is not always clear.

- Afo (Afao, Afu). They number about 8,000.

- Arago (Alago). They number about 15,000.

- Egede, with the Akweya, Yachi (Iyace), and detached Erulo. They number about 85,000.

- Gili (Koro of Lafia, Migili). They number about 7,000.

- Idoma, with the Agala, Agatu, Igumale, Okpoto (Akpoto), Okwaga, and Oturkpo. They number about 250,000.

- Igala (Atagara, Igara, Igula), with the Ibaji. They number about 200,000.

- Iyala (Ingkum, Yala), with the Nkum (Nkim). They number about 30,000.

Nupe Cluster

The tribes of this cluster speak languages of the Nupe branch of the Kwa subfamily of the igritic stock. Islam has been widely accepted.

- Igbira (Egbiri, Korokori), with the Tgu (Egu), Okene (Okeni), and Panda (Hima, Kwotto, Wushishi). They number about 250,000.

- Nge (Basange, Bassange). These people. numbering about 20,000, are an offshoot of the Nupe who fled to escape Fulani conquest.

- Nupe, embracing the Batache, Beni (Bini), Benu, Chakpang (Cakpang), Dibo (Ganagana, Zirako), Ebagi, Ebe (Abewa), Gbedye, Gwagba, Kakanda (Akanda, Hyapa), Kede (Kyedye), Kupa (Gupa), Kusopa, and Zam. They number about 360,000 and were conquered by the Fulani around 1820.

Central Cluster

The tribes of this cluster are linguistically somewhat diverse, though all speak Nigritic languages.

- Edo (Bini), with the Ishan (Esa, Isa). They number about 400,000 and belong to the Edo branch of the Kwa subfamily of the Nigricic stock.

- Ibo, embracing the Ada (Edda), Ika, Onitsha, and other subtribes. They number nearly 4 million, and constitute the Ibo branch of the Kwa linguistic subfamily.

- Ijaw (Ijo), with the Brass and Kalahari. They constitute the sole members of the Ijaw subfamily of the Nigritic linguistic stock. In 1921 they had a reported population of about 175,000.

- Tsoko, with the Erakwa and Urhobo (Sobo). They belong to the Edo branch of the Kwa linguistic subfamily and number about 435,000.

- Itsekiri (Awerri, Jakri, Jekri, Oere, Ouere, Owerri, Warri). They belong to the Yoruba branch of the Kwa linguistic subfamily. They number about 33,000 and subsist primarily by fishing.

- Kukuruku, embracing the Akoko, Etsako, Ineme, and Ivbiosakon subtribes. They number slightly under 200,000 and belong to the Edo branch of the Kwa linguistic subfamily.

Yoruba Cluster

The tribes of this cluster all speak closely related languages belonging to the Yoruba branch of the Kwa subfamily of the Nigritic stock. Most of them have been notably urban for centuries.

- Ana (Atakpame, Ife), with the Dume and Kpedji. This group, numbering about 15,000, split off from the Ife in the sixteenth century and migrated west into Togo and Dahomey.

- Bunu (Kabba), embracing the Aworo (Akanda), Bunu, ljumu (with the Ibbedde and Adda), Owe (Kabba), and Yagba. They number about 100,000.

- Egba, with the Awori (Dje, Holli), Badagri, Dassa, Egabo, Itsha (Tsha), Ketu, Manigri, Nago (Anago, Nagot), and Tshabe (Tschebe). They number about 550,000.

- Ekiti, with the Akoko, Ondo, and Owo-Ifon. They number about 370,000.

- Ife, with the Ilesha (Ijesha) and Illa. They number about 170.000.

- Ijebu, including the kindred inhabitants of Lagos and the adjacent coast. They number about 550,000.

- Yoruba proper, embracing the lbadan, Igbolo, lgbona (Igbomina), Ilorin, and Oyo. They number about 1,600,000. Islam is fairly widespread among the Ilorin, who were conquered by the Fulani in 1831.

Sudanic agriculture doubtless penetrated Southern Nigeria from the north at an early period. Since, however, its crops are not in general well suited to tropical-forest conditions, it probably replaced the earlier primary dependence upon hunting, fishing, and gathering only in favorable locations, especially along the northern fringe of the area. This is suggested by the surprisingly minor role which plants of the Sudanic complex play in the present economies. Sorghum and millet, for example, appear as staples only among the Nupe, and in many tribes are grown only sparingly or not at all. Akee, ambary, cotton, earth peas, fluted pumpkins, gourds, okra, sesame, and y ergan are cultivated fairly widely but not in great quantities. Guinea yams and especially the oil palm, however, are important, and these were presumably brought under cultivation originally on the coast rather than in the interior. Even though agriculture probably held only a subordinate place in the coastal economies for a long time, irs antiquity cannot be denied. Otherwise we could scarcely account for the fact that the cultivation of certain Sudanic crops, notably millet, is often heavily incrusted with ritual.

The arrival of the Malaysian complex by overland transmission from the east, which probably occurred around the beginning of the Christian era, must have wrought an explosive transformation in the economy. Population catapulted with the introduction of a new and abundant food supply, until today it is appreciably denser in this region than in any other part of the African continent. Yams proved particularly well adapted to local conditions and are today the outstanding staple in the majority of the tribes of the province. Taro, known locally as the coco yam, is likewise important everywhere, and in several tribes it rises to the status of a co-staple. Bananas constitute the chief crop of the Anyang but have achieved only a subsidiary position farther west.

The introduction of American cultivated plants from Brazil and the West Indies after 1500, mediated by the European slave traders, gave a new fillip to the economy. Being native to a similar environment in the New World, they readily became established on the Guinea coast. They soon outstripped the crops of the Sudanic complex and today are second only to those of the Malaysian complex. Peppers, pineapples, pumpkins, squash, sweet potatoes, tobacco, and tomatoes occur fairly widely, and maize, manioc, and peanuts rank among the mamstays of the pre ent economy. Among the Ijebu and Itsekiri, indeed, manioc have even supplanted yams as the principal crop.

Nearly all tribes keep a few cattle, but do not milk them. Goats, heep, dogs, and chickens are general, and there are occasional reports of horses, pigs, cats, ducks, and guinea fowl. Hunting and gathering are less productive today than formerly, but fishing adds an important increment to the food supply in most tribes and provides the primary basis of subsistence for the Itsekiri. Trade and handicraft indu tries are highly developed, and regular markets are practically uniersal. Men hunt, clear land for agriculture, and do most of the fishing, whereas women engage in market trading. Both sexes participate in cultivation, but men do more of the work among the western tribes, women among tho e in the east.

The Egede, most Ibo, and some Idoma live in neighborhoods of dispersed family homesteads, but most tribes occupy compact villages and towns. These are typically divided into wards, or quarters, which sometimes, as among the lbibio and Nupe, are physically separated as distinct hamlets. Anyang, Edo, and Ekoi villages often consist of a double row of habitations along a single village street. In the more populous tribes, settlements sometimes attain the size of true cities. Ibadan in the Yoruba country, for example, has a population of 400,000 and is the largest exclusively Negro city in all Africa. Cone-cylinder huts of the familiar Sudanic type prevail among the Boki and the tribes of the Idoma and Nupe clusters, which border the Plateau Nigerians, but elsewhere we encounter a new and distinctive house type—a rectangular dwelling with walls of mats or wattle and daub and a gable roof thatched with palm leaves. These houses are grouped in compounds around a central courtyard, usually rectangular in shape. Where huts are round, on the other hand, compounds tend to be circular.

All Southern Nigerians require a consideration in marriage. This consists primarily of bride-service and gifts among the Ekoi and Igbira and of a woman given in exchange among the Afo and some Idoma and Ibo, but it assumes the form of a substantial bride-price in all other groups. The Ijaw and Kukuruku, to be sure, permit marriages with but a minimal consideration as an alternative, but in such cases the children belong not to the father but to the mother's family. The Ekoi, Ibibio, and Ibo systematically fatten a girl for her wedding, sometimes for periods exceeding a year. The Ekoi and Nupe allow cousins to marry, and the Yako and eastern Ibo prefer unions with a father's sister's daughter, but most groups regard any cousin marriage as incestuous. Polygyny is favored by all the peoples of the region. The sororal form is permitted among the Idoma and Igala but forbidden in most other tribes. The first wife enjoys a preferred status, but each co-wife normally has a separate hut or apartment. Residence is regularly patrilocal, but the Yako require an initial matrilocal period, and the Kukuruku follow the avunculocal rule in certain instances. With only inconsequential exceptions the patrilocal extended family everywhere constitutes a strongly functional unit, though it may be composed of distinct polygynous households.

Descent, inheritance, and succession usually follow the patrilineal principle. Patrilineages are apparently universal, but among the rago, Egede, Idoma, Ttsekiri, and Nupe they are not exogamous. On the other hand, exogamy extends not only to lineages but also to sibs in the Yoruba cluster and among the Anyang, Edo, and Yako. Kin groups are nearly always localized as clans—usually in wards or barrios but occasionally in whole settlements, e.g., among the nyang and rago. Kinship terminology follows a number of different patterns: descriptive among the Ibibio, Hawaiian in the Edo and Yoruba groups, Iroquois among the Yako, and Omaha among the Ibo and Tgbira. The social systems of a few eastern tribes give internal evidence of possible former matrilineal descent. Among the Yako, for example, there are exogamous matrilineal as well as patrilineal sibs and lineages, and the rule of inheritance is matrilineal for movables though patrilineal for land. The adjacent Afikpo Ibo and some Ekoi also reveal double descent and mixed norms of inheritance, and the neighboring Mbembe, for whom matrilineal inheritance is reported, may well fall into the same category. Among the Kukuruku, descent depends upon the mode of marriage, being patrilineal when a bride-price has been paid for the mother but otherwise usually matrilineal.

Most Southern Nigerian tribes practice circumcision. Clitoridectomy is nearly as prevalent but is specifically denied for the Afo, Idoma, Ijaw, and Itsekiri tribes. Age-grades occur very widely but are not quite universal. Among the eastern Ibo, who may serve as an example, young men are organized into age-sets every third year in each village, where they engage in communal labor. Approximately every ninth year the three oldest sets, including men from thirty-five to forty-five years of age, are reconstituted as an age-grade, with police functions and the responsibility for executing the decisions of the village elders. After a period in this grade they are promoted to the first of three grades of “elders,” who exercise political authority not only in the village but also in the district.

States of considerable magnitude occur among the Edo, Igala, Igbira, Ijaw, ltsekiri, Nupe, and all tribes of the Yoruba cluster, but elsewhere political integration does not transcend the level of the local community with a headman and a council of elders or of a small district with an age-grade organization or a petty paramount chief. Among the tribes of the Idoma and Nupe clusters succession to chiefly positions commonly alternates among two or more royal lines. Slavery is universal, but differentiated royal and noble classes appear only in conjunction with a complex political organization. Elsewhere status depends upon seniority and especially on the acquisition of titles. These are commonly organized in elaborate hierarchical systems, in which titles of different grades are achievable in a defined order through feasts and large payments to the holders of higher titles. Human sacrifice is reported for the Arago, Bunu, Edo, Ibo, Igala, Ijaw, and Yoruba; cannibalism for the Boki, Ekoi, Ibo, and some Igbira and Ijaw; headhunting for the Boki, Egede, Ekiti, Ekoi, Ibo, Idoma, Igala, Igbira, Ijaw, Kukuruku, Nge, Orri, and some Iyala and Nupe.

The larger states are headed by absolute monarchs, who maintain elaborate courts in capital towns and rule their countries through administrative hierarchies of provincial governors and district chiefs. The heads of the Ife, Igala, and Igbira states are divine kings, whose persons are sacred, who are hedged in by a multitude of taboos, and who exercise sacerdotal as well as secular functions. Rulers are served by palace officials, who are often eunuchs, and by titled ministers, who commonly form a council of state. A Queen-Mother often maintains a separate court and retinue, and in the Igbira state of Panda a Queen-Sister holds an exalted position and the ranking Queen-Consort exercises authority over all the women of the palace. The Edo state of Benin, which was founded in the twelfth century and which conquered and subjugated most of the neighboring peoples in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, may be described in some detail as representative of the more complex political institutions of the region.

The Edo king maintains a court and a large harem at the capital city of Benin. Here he concerns himself primarily with state rituals, cult activities, and judicial cases. Queen-Mother and a Queen-Consort hold positions of great influence and prestige, as does the heir apparent, the ruler's eldest son. A hierarchical administrative organization assures the support of the state apparatus by levying corvée labor and collecting tribute semiannually in palm oil, livestock, and agricultural produce.

These sources of revenue are augmented by court fines, trade monopolies, fees received from prospective titleholder , and the booty obtained in war. Routine decisions are made by a supreme council of seven ranking ministers, including the heir apparent and the hereditary governors of the six major provinces. The latter also have specialized functions, e.g., as chief priest, commander in chief of the army, and keeper of the royal shrines. For decisions of greater moment they are joined by eighteen town chiefs and twenty-nine palace chiefs to form a grand council. All but one official in each of the latter categories hold their offices by appointment —as territorial administrators in the one case and as functionaries of the royal household in the other. Below them stand the holders of titles of numerous subsidiary orders, each of whom has obtained his original appointment and each promotion by the payment of generous fees.

Selected Bibliography